Risk And Diversification

The events of the past several days provide us all with an instructive backdrop for several important financial topics. Even folks who don’t routinely pay attention to financial goings-on are now likely to have heard about the collapse (and subsequent rescue) of Silicon Valley Bank.

The first and most obvious of these is a reminder that stock investing always comes with risks. When the economy is booming and companies are doing well, it’s easy to forget about risk. But it’s always there. That’s why the first thing we think about when investing in the stock market is how to manage risk.

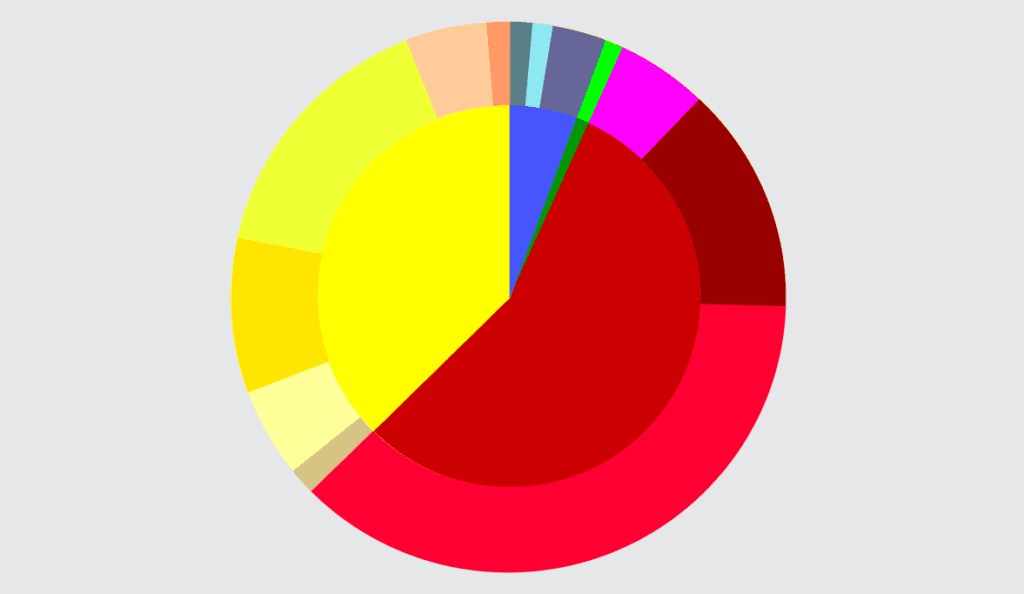

Much of the risk associated with stock investing is associated with price volatility (changing prices) in the marketplace. That’s a very general risk. But there is also the risk that one of the companies we’ve invested in fails and the stock therefore becomes worthless. Luckily, we can largely address such loss-of-capital risk through diversification – or not putting all of our eggs in one basket, as the old saying goes.

In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, depending on how events now unfold, the stock could still become worthless.

So what does that mean for the stock funds you hold? The answer is: not absolutely nothing, but also not very much. Here is the exposure to Silicon Valley Bank in our most frequently used funds as of January 31st, 2023:

- Core Equity 1 Portfolio DFEOX 0.0006

- Core Equity 2 Portfolio DFQTX 0.0007

- Core Equity 2 ETF DFAC 0.0006

- Core Equity Market ETF DFAU 0.0006

- Equity ETF DFUS 0.0004

- Sustainability Core 1 DFSIX 0.0008

In other words, your overall investment is to a large extent insulated from the bankruptcy of a single company.

The Question of Cash

Many of us still think of cash as physical currency. But of course it’s much more complicated than that. When you log into your bank account to see how much cash you have, what you’re technically seeing is a liability on the balance sheet of a bank, i.e., that bank’s promise to give you access to either physical currency or another form of electronic cash on demand [i]. And of course it’s that “on demand” promise that Silicon Valley Bank couldn’t keep, and that was the source of its recent downfall.

My first career was in banking, and so I’ve always been fascinated by the structure, workings, and risks inherent in our modern fractional reserve banking system. That said, I’m going to avoid a deep dive into those technical details here on the assumption that they would bore most of my readers to death. I do, however, suspect that many of you are asking yourselves: “So what could happen to the ‘cash’ in my brokerage account?” “Could something happen like what happened to the cash deposits in SVB?”

Good questions.

First of all, as a matter of philosophical principle, there is no such thing as “zero risk.” Even physical cash is subject to various risks, e.g., the risk of theft, risks associated with storage , a potential lost of purchasing power, political risk, etc. In other words, even if you’re wary of the banking system, keeping wads of 100-dollar bills under your mattress is probably even riskier.

I think better questions are: “Have we taken reasonable precautions to avoid as much risk to cash as possible?” and “How are we managing the tradeoffs between risk and return for the asset class of ‘cash’?”

To begin, there’s a technical detail that will be helpful for you to understand. Since Pershing is not a bank, what you see as cash in your Pershing brokerage account is not technically cash (i.e., a liability on the balance sheet of a bank). Instead, it is “near cash.” Near cash consists of vehicles that can be easily and seamlessly exchanged for cash at a 1-to-1 exchange rate. These vehicles are called “sweep funds” because cash is automatically “swept” in and out of them as needed. In other words, in all but the most extreme and bizarre circumstances, near cash walks like a duck and quacks like a duck even though it isn’t actually a duck. Which is why most of us ignore the differences most of the time.

The reason for understanding the distinction has to do with both risk and return.

Individual banks offer very different returns (interest) on the cash (deposits) they hold for you. Many people have noticed that deposits held at the largest US banks still offer almost zero returns, even in savings accounts. In many ways, therefore, this is arguably the worst of all possible ways to hold cash (assuming you have more than the FDIC limit). You are likely to get low returns on your cash holdings, plus all of your eggs are in a single bank’s basket—which is unlikely to be risky but can be, as SVB customers just experienced.

At Griffin Black we use several different near cash alternatives, depending on the client, the account, and the situation.

- A bank-deposit fund. This is a vehicle that distributes your very large cash holdings among different banks so as to maintain FDIC deposit insurance on amounts over the $250,000/individual limit. These funds typically yield more than deposits at individual major banks, while providing higher per-person FDIC insurance. So if you sell your home and need to park the cash proceeds pending the purchase of a new one, this is probably a good option for you.

- A high quality money market fund. Most of us understand this concept. Money market funds hold a large and highly diversified portfolio of short-term, high-quality government and commercial paper. A few of them had performance issues during the financial crisis, but regulations have improved since then. As a result, money market funds currently offer much higher interest rates than most large banks, including rates offered by bank deposit funds, and are subject to very low risk. We currently use very conservative money market funds as the near cash alternative for most of our investment accounts.

- For clients who have very large amounts of cash and want the highest available yields consistent with safety over a specific time horizon, we can purchase individual US Treasury securities. This is a choice that we typically make in direct consultation with a client since it does entail a question of an appropriate holding period. But short-term interest rates offered by the US government haven’t been this high since the late 1970s/early 1980s and can offer an excellent choice of where to park cash with extremely limited risk.

- Finally, our clients have access to Flourish Cash. These accounts are directly linked to existing bank accounts and are not associated with investment accounts per se. But, like the bank deposit funds described above, they distribute account holders’ cash among participating banks while maintaining FDIC insurance. Interest offered floats, but is currently far higher than that offered by most large banks.

If you have questions or concerns regarding these or other aspects of your portfolios, your Griffin Black advisor is always here to help.

[i] This is why traditional checking accounts are referred to in the industry as DDAs, or “Demand Deposit Accounts.”

2 thoughts on “Special Edition: Is My Money Safe?”

Dearest Jane,

I just read this article and really enjoyed it. It was informative and easy to understand. Thank you! In addition to understanding the current cash situation better, I also totally understand that you are a geek in this stuff, and we are very happy to have you!????????

❤️Beth and Lydia

Hi Beth. I’m so glad you enjoyed the article! I hope it helped you better understand your cash holdings and feel a bit more secure when other kinds of assets are ‘misbehaving.’ -Jane